The Carrying Read online

Page 4

collect them, pin their glossy backs

to the board like the rows of stolen

beauties, dead, displayed at Isla Negra,

where the waves broke over us

and I still loved the country, wanted

to suck the bones of the buried.

Now, I’m outside a normal house

while friends cook and please

and pour secrets into each other.

A crow pierces the sky, ominous,

clanging like an alarm, but there

is no ocean here, just tap water

rising in the sink, a sadness clean

of history only because it’s new,

a few weeks old, our national wound.

I don’t know how to hold this truth,

so I kill it, pin its terrible wings down

in case, later, no one believes me.

FULL GALLOP

The night after, I dream I chop

all the penises off, the ones that

keep coming through the walls.

Tied in sweat-wet sheets, I wake

aching, how I’ve longed for touch

for so much of my bodied time.

In the shower later, I notice new

layers I’ve grown, softness love tosses

you after years of streetlights alone.

I will never harm you, your brilliant

skin I rub against in the night,

still, part of me is haunted—

a shadow baying inside me

who wants to snap her hind leg

back, buck the rider, follow

that fugitive call into oblivion.

DREAM OF THE MEN

At the beach that was so gray it seemed stone—

gray water, gray sky, gray blanket, and the wind

some sort of gray perpetual motion machine—

we gathered like a blustery coven on the blanket

from Mexico woven with white and gray threads

into a pattern of owls and great seabirds. Then,

they came: the men. Blankets full of them, talking,

talking, talking, talking, and our mouths were sewn

shut with patient smiles while they talked about

the country where they were from; their hands

like slick seaweed were everywhere, unwelcome,

multicellular, touching us.

A NEW NATIONAL ANTHEM

The truth is, I’ve never cared for the National

Anthem. If you think about it, it’s not a good

song. Too high for most of us with “the rockets’

red glare” and then there are the bombs.

(Always, always there is war and bombs.)

Once, I sang it at homecoming and threw

even the tenacious high school band off key.

But the song didn’t mean anything, just a call

to the field, something to get through before

the pummeling of youth. And what of the stanzas

we never sing, the third that mentions “no refuge

could save the hireling and the slave”? Perhaps

the truth is every song of this country

has an unsung third stanza, something brutal

snaking underneath us as we blindly sing

the high notes with a beer sloshing in the stands

hoping our team wins. Don’t get me wrong, I do

like the flag, how it undulates in the wind

like water, elemental, and best when it’s humbled,

brought to its knees, clung to by someone who

has lost everything, when it’s not a weapon,

when it flickers, when it folds up so perfectly

you can keep it until it’s needed, until you can

love it again, until the song in your mouth feels

like sustenance, a song where the notes are sung

by even the ageless woods, the shortgrass plains,

the Red River Gorge, the fistful of land left

unpoisoned, that song that’s our birthright,

that’s sung in silence when it’s too hard to go on,

that sounds like someone’s rough fingers weaving

into another’s, that sounds like a match being lit

in an endless cave, the song that says my bones

are your bones, and your bones are my bones,

and isn’t that enough?

CARGO

I wish I could write to you from underwater,

the warm bath covering my ears—

one of which has three marks in the exact

shape of a triangle, my own atmosphere’s asterism.

Last night, the fire engine sirens were so loud

they drowned out even the constant bluster

of the inbound freight trains. Did I tell you,

the R. J. Corman Railroad runs 500 feet from us?

Before everything shifted and I aged into this body,

my grandparents lived above San Timoteo Canyon

where the Southern Pacific Railroad roared each scorching

California summer day. I’d watch for the trains,

howling as they came.

Manuel is in Chicago today, and we’ve both admitted

that we’re traveling with our passports now.

Reports of ICE raids and both of our bloods

are requiring new medication.

I wish we could go back to the windy dock,

drinking pink wine and talking smack.

Now, it’s gray and pitchfork.

The supermarket here is full of grass seed like spring

might actually come, but I don’t know. And you?

I heard from a friend that you’re still working on saving

words. All I’ve been working on is napping, and maybe

being kinder to others, to myself.

Just this morning, I saw seven cardinals brash and bold

as sin in a leafless tree. I let them be for a long while before

I shook the air and screwed it all up just by being alive too.

Am I braver than those birds?

Do you ever wonder what the trains carry? Aluminum ingots,

plastic, brick, corn syrup, limestone, fury, alcohol, joy.

All the world is moving, even sand from one shore to another

is being shuttled. I live my life half afraid, and half shouting

at the trains when they thunder by. This letter to you is both.

THE CONTRACT SAYS: WE’D LIKE THE CONVERSATION TO BE BILINGUAL

When you come, bring your brownness

so we can be sure to please

the funders. Will you check this

box; we’re applying for a grant.

Do you have any poems that speak

to troubled teens? Bilingual is best.

Would you like to come to dinner

with the patrons and sip Patrón?

Will you tell us the stories that make

us uncomfortable, but not complicit?

Don’t read us the one where you

are just like us. Born to a green house,

garden, don’t tell us how you picked

tomatoes and ate them in the dirt

watching vultures pick apart another

bird’s bones in the road. Tell us the one

about your father stealing hubcaps

after a colleague said that’s what his

kind did. Tell us how he came

to the meeting wearing a poncho

and tried to sell the man his hubcaps

back. Don’t mention your father

was a teacher, spoke English, loved

making beer, loved baseball, tell us

again about the poncho, the hubcaps,

how he stole them, how he did the thing

he was trying to prove he didn’t do.

IT’S HARDER

Not to unravel the intentions of the other—

the slight gestur

e over the coffee table, a raised

eyebrow at the passing minuscule skirt, a wick

snuffed out at the evening’s end, a sympathetic

nod, a black garbage can rolled out so slowly

he hovers there, outside, alone, a little longer,

the child’s thieving fingers, the face that’s serene

as cornfields, the mouth screwed into a plum,

the way I can’t remember which blue lake

has the whole train underneath its surface,

so now, every blue lake has a whole train

underneath its surface.

3

AGAINST BELONGING

It’s been six years since we moved here, green

of the tall grasses outstretched like fingers waving.

I remember the first drive in; the American beech,

sassafras, chestnut oak, yellow birch were just

plain trees back then. I didn’t know we’d stay long.

I missed the Sonoma coast line, the winding

roads that opened onto places called Goat Rock,

Furlong Gulch, Salmon Creek. Once, when I was

young, we camped out at Russian Gulch and learned

the names of all the grasses, the tide pool animals,

the creatures of the redwoods, properly identifying

seemed more important than science, more like

creation. With each new name, the world expanded.

I give names to everything now because it makes

me feel useful. Currently, three snakes surround our

house. One in front, one near the fire pit, and one

near the raised beds of beets and carrots. Harmless

Eastern garter snakes, small, but ever expanding.

I check on them each day, watch their round eyes

blink in the sun that fuels them. I’ve named them

so no one is tempted to kill them (a way of offering

reprieve, tenderness). But sometimes I feel them

moving around inside me, the three snakes hissing—

what cannot be tamed, what shakes off citizenship,

what draws her own signature with her body

in whatever dirt she wants.

INSTRUCTIONS ON NOT GIVING UP

More than the fuchsia funnels breaking out

of the crabapple tree, more than the neighbor’s

almost obscene display of cherry limbs shoving

their cotton candy–colored blossoms to the slate

sky of spring rains, it’s the greening of the trees

that really gets to me. When all the shock of white

and taffy, the world’s baubles and trinkets, leave

the pavement strewn with the confetti of aftermath,

the leaves come. Patient, plodding, a green skin

growing over whatever winter did to us, a return

to the strange idea of continuous living despite

the mess of us, the hurt, the empty. Fine then,

I’ll take it, the tree seems to say, a new slick leaf

unfurling like a fist, I’ll take it all.

WOULD YOU RATHER

Remember that car ride to Sea-Tac, how your sister’s kids

played a frenzied game of Would You Rather, where each choice

ticktocked between superpowers or towering piles of a food

too often denied, Would You Rather

have fiery lasers that shoot out of your eyes,

or eat sundaes with whip cream for every meal?

We dealt it out quick,

without stopping to check ourselves for the truth.

We played so hard that I got good at the questions, learned

there had to be an equality

to each weighted ask. Now I’m an expert at comparing things

that give the illusion they equal each other.

You said our Plan B was just to live our lives:

more time, more sleep, travel—

and still I’m making a list of all the places

I found out I wasn’t carrying a child.

At the outdoor market in San Telmo, Isla Negra’s wide iris of sea,

the baseball stadium, the supermarket,

the Muhammad Ali museum, but always

the last time tops the list, in the middle of the Golden Gate Bridge,

looking over toward Alcatraz, a place they should burn and redeliver

to the gulls and cormorants, common daisies and seagrass.

Down below the girder that’s still not screened against jumpers,

so that it seems almost like a dare, an invitation,

we watched a seal make a sinuous shimmy in the bay.

Would you rather? Would I rather?

The game is endless and without a winner.

Do you remember how the seal was so far under

the deafening sound of traffic, the whir of wind mixed

with car horns and gasoline, such a small

speck of black movement alone in the churning waves

between rock and shore?

Didn’t she seem happy?

MAYBE I’LL BE ANOTHER KIND OF MOTHER

Snow today, a layer outlining the maple like a halo,

or rather, a fungus. So many sharp edges in the month.

I’m thinking I’ll never sit down at the table

at the restaurant, you know that one, by the window?

Women gathered in paisley scarves with rusty iced tea,

talking about their kids, their little time-suckers,

how their mouths want so much, a gesture of exhaustion,

a roll of the eyes, But I wouldn’t have it any other way,

their bags full of crayons and nut-free snacks, the light

coming in the window, a small tear of joy melting like ice.

No, I’ll be elsewhere, having spent all day writing words

and then at the movies, where my man bought me a drink,

because our bodies are our own, and what will it be?

A blockbuster? A man somewhere saving the world, alone,

with only the thought of his family to get him through.

The film will be forgettable, a thin star in a blurred sea of stars,

I’ll come home and rub my whole face against my dog’s

belly; she’ll be warm and want to sleep some more.

I’ll stare at the tree and the ice will have melted, so

it’s only the original tree again, green branches giving way

to other green branches, everything coming back to life.

CARRYING

The sky’s white with November’s teeth,

and the air is ash and woodsmoke.

A flush of color from the dying tree,

a cargo train speeding through, and there,

that’s me, standing in the wintering

grass watching the dog suffer the cold

leaves. I’m not large from this distance,

just a fence post, a hedge of holly.

Wider still, beyond the rumble of overpass,

mares look for what’s left of green

in the pasture, a few weanlings kick

out, and theirs is the same sky, white

like a calm flag of surrender pulled taut.

A few farms over, there’s our mare,

her belly barrel-round with foal, or idea

of foal. It’s Kentucky, late fall, and any

mare worth her salt is carrying the next

potential stakes winner. Ours, her coat

thicker with the season’s muck, leans against

the black fence and this image is heavy

within me. How my own body, empty,

clean of secrets, knows how to carry her,

knows we were all meant for something.

WHAT I DIDN’T KNOW BEFORE

was how horses simply give birth to other

horses. Not a baby by any means, not

a creature of

liminal spaces, but already

a four-legged beast hellbent on walking,

scrambling after the mother. A horse gives way

to another horse and then suddenly there are

two horses, just like that. That’s how I loved you.

You, off the long train from Red Bank carrying

a coffee as big as your arm, a bag with two

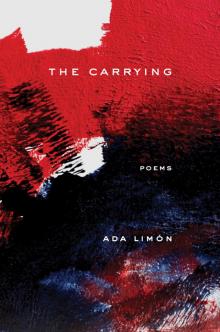

The Carrying

The Carrying