The Carrying Read online

ALSO BY ADA LIMÓN

Lucky Wreck

This Big Fake World

Sharks in the Rivers

Bright Dead Things

© 2018, Text by Ada Limón

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher: Milkweed Editions, 1011 Washington Avenue South, Suite 300, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55415.

(800) 520-6455

milkweed.org

Published 2018 by Milkweed Editions

Printed in Canada

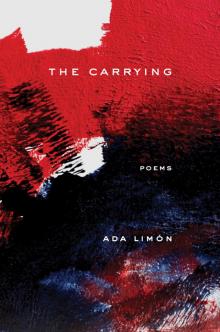

Cover design by Mary Austin Speaker

Cover art by Stacia Brady

Author photo by Lucas Marquardt

18 19 20 21 22 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

Milkweed Editions, an independent nonprofit publisher, gratefully acknowledges sustaining support from the Jerome Foundation; the Lindquist & Vennum Foundation; the McKnight Foundation; the National Endowment for the Arts; the Target Foundation; and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. Also, this activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund, and a grant from Wells Fargo. For a full listing of Milkweed Editions supporters, please visit milkweed.org.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Limón, Ada, author.

Title: The carrying: poems / Ada Limón.

Description: First edition. | Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017061361 (print) | LCCN 2018002212 (ebook) | ISBN 9781571319944 (ebook) | ISBN 9781571315120 (hardcover: acid-free paper)

Classification: LCC PS3612.I496 (ebook) | LCC PS3612.I496 A6 2018 (print) | DDC 811/.6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017061361

Milkweed Editions is committed to ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book production practices with this principle, and to reduce the impact of our operations in the environment. We are a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit coalition of publishers, manufacturers, and authors working to protect the world’s endangered forests and conserve natural resources. The Carrying was printed on acid-free 100% postconsumer-waste paper by Friesens Corporation.

For Lucas & Lily Bean

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1.

A Name

Ancestors

How Most of the Dreams Go

The Leash

Almost Forty

Trying

On a Pink Moon

The Raincoat

The Vulture & the Body

American Pharoah

Dandelion Insomnia

Dream of the Raven

The Visitor

Late Summer after a Panic Attack

Bust

Dead Stars

Dream of Destruction

Prey

2.

The Burying Beetle

How We Are Made

The Light the Living See

The Dead Boy

What I Want to Remember

Overpass

The Millionth Dream of Your Return

Bald Eagles in a Field

I’m Sure about Magic

Wonder Woman

The Real Reason

The Year of the Goldfinches

Notes on the Below

Sundown & All the Damage Done

On a Lamppost Long Ago

Of Roots & Roamers

Killing Methods

Full Gallop

Dream of the Men

A New National Anthem

Cargo

The Contract Says: We’d Like the Conversation to Be Bilingual

It’s Harder

3.

Against Belonging

Instructions on Not Giving Up

Would You Rather

Maybe I’ll Be Another Kind of Mother

Carrying

What I Didn’t Know Before

Mastering

The Last Thing

Love Poem with Apologies for My Appearance

Sway

Sacred Objects

Sometimes I Think My Body Leaves a Shape in the Air

Cannibal Woman

Wife

From the Ash inside the Bone

Time Is On Fire

After the Fire

Losing

The Last Drop

After His Ex Died

Sparrow, What Did You Say?

Notes & Acknowledgments

About the Author

She had some horses she loved.

She had some horses she hated.

These were the same horses.

JOY HARJO

1

A NAME

When Eve walked among

the animals and named them—

nightingale, red-shouldered hawk,

fiddler crab, fallow deer—

I wonder if she ever wanted

them to speak back, looked into

their wide wonderful eyes and

whispered, Name me, name me.

ANCESTORS

I’ve come here from the rocks, the bone-like chert,

obsidian, lava rock. I’ve come here from the trees—

chestnut, bay laurel, toyon, acacia, redwood, cedar,

one thousand oaks

that bend with moss and old-man’s beard.

I was born on a green couch on Carriger Road between

the vineyards and the horse pasture.

I don’t remember what I first saw, the brick of light

that unhinged me from the beginning. I don’t remember

my brother’s face, my mother, my father.

Later, I remember leaves, through car windows,

through bedroom windows, through the classroom window,

the way they shaded and patterned the ground, all that

power from roots. Imagine you must survive

without running? I’ve come from the lacing patterns of leaves,

I do not know where else I belong.

HOW MOST OF THE DREAMS GO

First, it’s a fawn dog, and then

it’s a baby. I’m helping him

to swim in a thermal pool,

the water is black as coffee,

the cement edges are steep

so to sink would be easy

and final. I ask the dog

(that is also the child),

Is it okay that I want

you to be my best friend?

And the child nods.

(And the dog nods.)

Sometimes, he drowns.

Sometimes, we drown together.

THE LEASH

After the birthing of bombs of forks and fear,

the frantic automatic weapons unleashed,

the spray of bullets into a crowd holding hands,

that brute sky opening in a slate-metal maw

that swallows only the unsayable in each of us, what’s

left? Even the hidden nowhere river is poisoned

orange and acidic by a coal mine. How can

you not fear humanity, want to lick the creek

bottom dry, to suck the deadly water up into

your own lungs, like venom? Reader, I want to

say: Don’t die. Even when silvery fish after fish

comes back belly up, and the country plummets

into a crepitating crater of hatred, isn’t there still

something singing? The truth is: I don’t know.

/>

But sometimes I swear I hear it, the wound closing

like a rusted-over garage door, and I can still move

my living limbs into the world without too much

pain, can still marvel at how the dog runs straight

toward the pickup trucks breaknecking down

the road, because she thinks she loves them,

because she’s sure, without a doubt, that the loud

roaring things will love her back, her soft small self

alive with desire to share her goddamn enthusiasm,

until I yank the leash back to save her because

I want her to survive forever. Don’t die, I say,

and we decide to walk for a bit longer, starlings

high and fevered above us, winter coming to lay

her cold corpse down upon this little plot of earth.

Perhaps we are always hurtling our bodies toward

the thing that will obliterate us, begging for love

from the speeding passage of time, and so maybe,

like the dog obedient at my heels, we can walk together

peacefully, at least until the next truck comes.

ALMOST FORTY

The birds were being so bizarre today,

we stood static and listened to them insane

in their winter shock of sweet gum and ash.

We swallow what we won’t say: Maybe

it’s a warning. Maybe they’re screaming

for us to take cover. Inside, your father

seems angry, and the soup’s grown cold

on the stove. I’ve never been someone

to wish for too much, but now I say,

I want to live a long time. You look up

from your work and nod. Yes, but

in good health. We turn up the stove

again and eat what we’ve made together,

each bite an ordinary weapon we wield

against the shrinking of mouths.

TRYING

I’d forgotten how much

I like to grow things, I shout

to him as he passes me to paint

the basement. I’m trellising

the tomatoes in what’s called

a Florida weave. Later, we try

to knock me up again. We do it

in the guest room because that’s

the extent of our adventurism

in a week of violence in Florida

and France. Afterward,

the sun still strong though lowering

inevitably to the horizon, I check

on the plants in the back, my

fingers smelling of sex and tomato

vines. Even now, I don’t know much

about happiness. I still worry

and want an endless stream of more,

but some days I can see the point

in growing something, even if

it’s just to say I cared enough.

ON A PINK MOON

I take out my anger

And lay its shadow

On the stone I rolled

Over what broke me.

I plant three seeds

As a spell. One

For what will grow

Like air around us,

One for what will

Nourish and feed,

One for what will

Cling and remind me—

We are the weeds.

THE RAINCOAT

When the doctor suggested surgery

and a brace for all my youngest years,

my parents scrambled to take me

to massage therapy, deep tissue work,

osteopathy, and soon my crooked spine

unspooled a bit, I could breathe again,

and move more in a body unclouded

by pain. My mom would tell me to sing

songs to her the whole forty-five-minute

drive to Middle Two Rock Road and forty-

five minutes back from physical therapy.

She’d say that even my voice sounded unfettered

by my spine afterward. So I sang and sang,

because I thought she liked it. I never

asked her what she gave up to drive me,

or how her day was before this chore. Today,

at her age, I was driving myself home from yet

another spine appointment, singing along

to some maudlin but solid song on the radio,

and I saw a mom take her raincoat off

and give it to her young daughter when

a storm took over the afternoon. My god,

I thought, my whole life I’ve been under her

raincoat thinking it was somehow a marvel

that I never got wet.

THE VULTURE & THE BODY

On my way to the fertility clinic,

I pass five dead animals.

First a raccoon with all four paws to the sky

like he’s going to catch whatever bullshit load

falls on him next.

Then, a grown coyote, his golden furred body soft against the white

cement lip of the traffic barrier. Trickster no longer,

an eye closed to what’s coming.

Close to the water tower that says “Florence, Y’all,” which means

I’m near Cincinnati, but still in the bluegrass state,

and close to my exit, I see

three dead deer, all staggered but together, and I realize as I speed

past in my death machine that they are a family. I say something

to myself that’s between a prayer and a curse—how dare we live

on this earth.

I want to tell my doctor about how we all hold a duality

in our minds: futures entirely different, footloose or forged.

I want to tell him how lately, it’s enough to be reminded that my

body is not just my body, but that I’m made of old stars and so’s he,

and that last Tuesday,

I sat alone in the car by the post office and just was

for a whole hour, no one knowing how to find me, until

I got out, the sound of the car door shutting like a gun,

and mailed letters, all of them saying, Thank you.

But in the clinic, the sonogram wand showing my follicles, he asks

if I have any questions, and says, Things are getting exciting.

I want to say, But what about all the dead animals?

But he goes quicksilver, and I’m left to pull my panties up like a big girl.

Some days there is a violent sister inside of me, and a red ladder

that wants to go elsewhere.

I drive home on the other side of the road, going south now.

The white coat has said I’m ready, and I watch as a vulture

crosses over me, heading toward

the carcasses I haven’t properly mourned or even forgiven.

What if, instead of carrying

a child, I am supposed to carry grief?

The great black scavenger flies parallel now, each of us speeding,

intently and driven, toward what we’ve been taught to do with death.

AMERICAN PHAROAH

Despite the morning’s gray static of rain,

we drive to Churchill Downs at 6 a.m.,

eyes still swollen shut with sleep. I say,

Remember when I used to think everything

was getting better and better? Now I think

it’s just getting worse and worse. I know it’s not

what I’m supposed to say as we machine our

way through the silent seventy minutes on 64

over potholes still oozing from the winter’s

wreckage. I’m tired. I’ve had vertigo for five

months and on my first day home, he’s shaken

me awake to see this horse not even race, but

work. He gives me his jacket as we face

the deluge from car to the Twin Spire turnstiles,

and once deep in the fern-green grandstands I see

the crowd. A few hundred maybe, black umbrellas,

cameras, and notepads, wet-winged eager early birds

come to see this Kentucky-bred bay colt with his

chewed-off tail train to end the almost forty-year

American Triple Crown drought. A man next to us,

some horse racing bigwig, hisses a list of reasons

why this horse—his speed-heavy pedigree, muscle

and bone recovery, etcetera etcetera could never

The Carrying

The Carrying